Now that I have the body cut, I can repair the limited amount of bodywork that needs replacing. I don’t want to start with replacing the A-Pillar sections that I found in the original inspection. I’m a bit paranoid about warping the shell, so I’m going to start with some of the smaller, non-structural welding repairs first. Well, I thought it would be non-structural, but I quickly found the rot had crawled into the suspension turret.

What is the scuttle?

I keep getting told off for using the term ‘scuttle’, and on reflection, it’s not especially clear if you’re not a #weirdcartwitter sort of person. According to a quick Google search, it looks like scuttle, when talking about a car, is a very British term;

Scuttle : The part of a car’s bodywork between the windscreen and the bonnet.

Definition from Oxford Languages

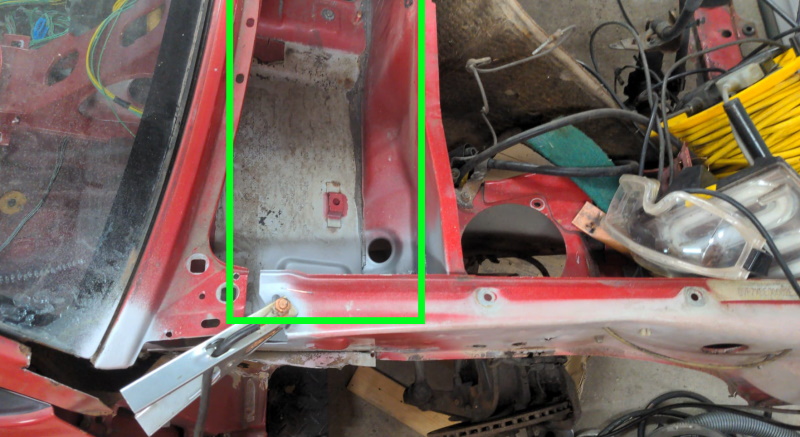

When I talk about the scuttle, I usually mean the area between the bottom of the windscreen and the engine bay that’s boxed off under the bonnet. The area in green in the picture below is, to me, the scuttle.

The ends of the BX scuttle house the front and rear washer bottle and are a common area for rust. There is normally rust here because it is such a complex area of the body. There are about six different panels here and a lot of factory seam sealant. Coupled with this, the area under the washer bottles often catches and hides leaves. As these break down, they tend to trap a lot of water. Once the paint is split, the water sat on top of the panel soon works its way to the steel and starts to rust.

The picture above shows how the driver’s end of the scuttle on XPO looked when it arrived. There are several reasons why the rust starts here. Personally, I think it’s down to the washer bottle. They have a rib on the bottom that always has a rough finish. That sharp-edged bit of plastic sits against the paint in this area and probably wears through as it vibrates. I’ve also noticed that this area is nearly always downhill from the drain hole, probably adding to the pooling water.

Preparing the scuttle

Before I can start to fill the hole, I need to cut the metalwork back to something I can weld to. Of the four BX’s I’ve had with rot in this area, it is normally contained in a single panel. This is the firewall panel, the vertical piece that separates the engine bay from the scuttle. Well, there is only one way to find the good metal, bring out the grinder!

After the first cut with the grinder, I then drilled out the spot welds, and there are quite a few here. The two that hold the firewall panel to the suspension turret top don’t need drilling. They fall away. Not a good sign. After a bit of cutting, I discovered the reinforced panel that makes up the suspension turret panel has a rotten edge. This is a 2mm piece of steel, and I’ve not come across rot here before. All of a sudden, the ‘it’s not structural‘ idealism is turned on its head!

The rot in the firewall panel isn’t too bad, but it runs into the bend in the panel. Trying to cut this panel at the point the rot finishes will be difficult because of access. And because of the sealant between the firewall panel and the suspension turret panel, direct welding is just going to create fire. So instead, I need to cut the firewall panel a few inches up from where it meets the suspension turret panel.

In the UK, the rot in the suspension turret would be considered an MOT failure if it was detected. Perhaps more critically, this will only get worse if it is not dealt with now. Once cut back to the good metal, this should be a simple enough repair and being a 2mm piece of plate. This repair will also be a good place to get my welding eye back in.

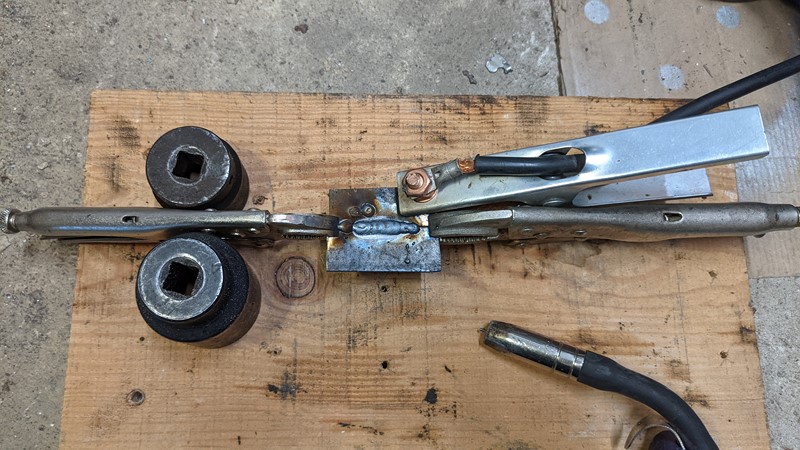

Firing up the Quattro welder

It’s been a while since I’ve put the welder onto the then metal of a Citroen BX. And the setup on the welder has changed too with thinner wire (0.6mm) and different gas (Hobby Weld). It’s at times like this that I like to have a little practice. So into the scrap bin, I delve!

I seem to find my feet with the power settings and wire feed straight away. This is less an accident and more a result of making notes every time I’m welding. A table of what works and does not speeds things up dramatically for an occasional welder like me. It’s not the biggest test piece, but it’s enough to gain some confidence.

And flipping it over, there is plenty of penetration. Perhaps not quite enough at the start, a reminder that I need to get some heat into the metal when I start the welding. I’m much more interested in a functional weld than a pretty weld. In my mind, a little too much penetration is better than non enough. But not forgetting that too much penetration causes damage to the surrounding metal, it’s all a balancing act.

Welding a repair into the suspension turret

The rust in the suspension turret is, fortunately, contained within a small accessible section. So it was simple enough to cut the bad piece out in one go, to give a template for the repair panel. Amazingly I didn’t have any 2mm pieces in the scraps bin.

Instead, this small repair slip is taken off a new sheet of metal. Being such a small piece, I braved the angle grinder and a 1mm cutting disc. I then cleaned the repair piece on a belt sander. I’m a big fan of welding clean metal and like to take the time to get a decent clean edge or two.

A pretty good fit first time, if I do say so myself. The repair piece is deliberately undersized, as I find this is more efficient than trying to get a perfect piece by repeated trimming. The gap also minimises the warping of the panels when the heat gets in from welding. However, it does risk the welding wire escaping off through the gap when triking up an arc.

To get the first tack welds in, I’m using a magnetic clamp underneath to hold it in place. This worked quite nicely, and the repair plate is tacked into a perfect position. Now what I should have done at this point was take the magnetic clamp off. The thing about liquid metal, like the sort you create while welding, is that it tends to be drawn towards a magnet.

And that’s exactly what happened on the outboard side of the suspension turret repair, on the left of the picture above. The molten metal was pulled into the magnet leaving a hole. Lesson learned. The penetration was a little less than ideal, so I went over the underside to get it well and truly stuck. Not the most beautiful, but functional.

Tidying up the suspension turret weld lines

As the top side of the suspension turret panel will have the firewall panel directly on top of it, I need to get the weld reasonably flat. Usually, I like to leave the non-visible welds proud. However, flattening off the welds takes a long time. If it’s rushed, there is a risk of removing too much and making the join weak. It’s a process that could, of course, be simplified with a bit more welding skill.

To take the grinds down, I take a multi-step approach. Getting the biggest blobs knocked down with a grinding disc, yes, I actually use a grinder for something other than cutting! Then a sanding flap wheel on a grinder to get the weld close to flush.

This approach works pretty well on the underside. I’ve left the weld line slightly high so as not to impair the strength of the join. This will be covered with etching primer, paint, topcoat and stone chip so the raised weld line won’t be noticeable.

The top side is a little trickier. The enclosed area in the scuttle makes it impossible to get a grinder in. In the end, I finish tidying the weld line with a finger sander with great success. While relatively slow going, the 12mm width of the finger sander makes it fantastic for getting into the tightest areas.

What’s next in the weldathon?

With the suspension turret welding complete, the next step will be to repair the hole in the firewall. The body cut will help here, offering a template for the missing piece of the panel. This, coupled with a bit of Cardboard Aided Design (CAD), should let me make up a pretty much perfect repair piece for the hole. There is a bit more rust to tackle in the scuttle too.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the return of XPO to the road is starting to fall behind schedule, but perhaps that’s no bad thing. No one wants to buy a car in the winter. The spring will be a much better time!

M

NEXT – Welding the scuttle Part 1

PREV – Repair Panel Body Cut